Swaps in the financial industry are complex derivative contracts that are essential in today's financial markets. With a focus on its key characteristics, uses, and roles, this abstract gives a general introduction to swaps.

What are Swaps?

Swaps are written agreements between two parties to exchange financial contracts over a specified period. They are based on credit events such as interest rates, currencies, equities, commodities, etc. The fundamental idea of a swap is to allow participants to choose their financial exposure, allowing them to adjust their risk and return profiles to meet their specific requirements. These agreements define the terms and conditions, the calculation method to be included, and the date. Swaps are also used for risk management, financial position optimization, or the achievement of specific financial goals.

Swaps are categorized into two types:

- Plain vanilla interest rate swaps: One of the most basic and often utilized forms of swaps in the financial markets is a plain vanilla interest rate swap. It includes two parties agreeing to exchange interest payments based on a notional principal amount for a given time.

There are two parties involved:

The "fixed-rate payer" agrees to pay interest at a set rate for the duration of the exchange.

“Floating-Rate Payer", agrees to pay an interest rate that is variable or floating and is based on an initial interest rate plus a spread, such as LIBOR or a national interbank rate.

Earlier LIBOR benchmark was used for financial exchanges. Currently, the replacement for the LIBOR benchmark is SOFR. In the United States, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) has mainly replaced the LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) benchmark, and several other locations have also developed their own replacement reference rates. These replacement rates were developed in order to address LIBOR's drawbacks and potential manipulation risks.

- Fixed-for-fixed Currency Swaps: A "fixed-for-fixed" currency swap is one where both parties agree to trade fixed interest rate payments in various currencies over a predetermined time period. The principal amount (notional amount) in this kind of currency swap is not changed; it remains the same the entire time the swap is in place. Instead, only the interest rate payments are being considered.

Let’s consider an example:

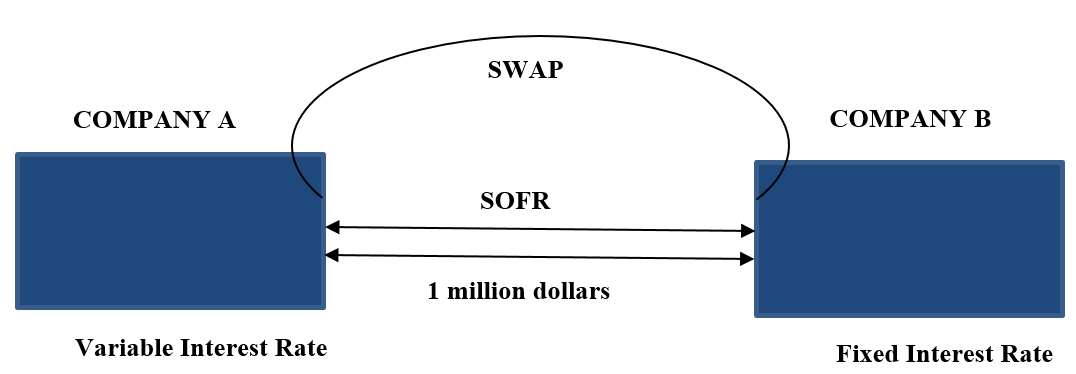

Let's consider two hypothetical companies, Company A and Company B, each with different preferences for interest rate structures. Both companies are considering a financial transaction involving $1 million and are looking to manage their interest rate risk using SOFR. Company A prefers fixed-rate financing to have predictable cash flows and reduce interest rate risk. They currently hold a $1 million loan with a variable interest rate. Similarly, Company B prefers floating-rate financing but is concerned about potential interest rate increases impacting their interest expenses. They also have a $1 million loan with a fixed interest rate.

Company A and Company B decide to enter into an interest rate swap agreement to align their financing preferences.

Note: When the swap is initiated, the fixed rate and the floating rate will have the same interest rate.

For the purpose of this example, we will assume that the SOFR 12-month rate when the swap is initiated is 2%.

Company A (Fixed-Rate Payer): Company A agrees to pay Company B a fixed interest rate of 4% per annum on a notional amount of $1 million.

Company B (Floating-Rate Payer): Company B agrees to pay Company A a floating interest rate based on SOFR plus a spread of 2% per annum on the same notional amount of $1 million.

The resulting interest swap will be:

Company A (Fixed-Rate Payer): Company A makes fixed interest payments of $40,000 per annum (4% of $1 million) to Company B.

Company B (Floating-Rate Payer): Company B makes floating interest payments to Company A based on SOFR plus a spread of 2%. These payments will vary based on the SOFR rate.

Through this interest rate swap, both companies achieve their financing objectives.

Company A gains interest rate stability.

Company B continues to benefit from floating-rate financing while having a fixed-rate hedge.

What are the mechanics involved in swap interest rate?

In order to structure and control swap transactions, several parts of contractual agreements are involved in the mechanics of swaps. The terms and conditions and payment mechanisms are two essential parts of these agreements: The interest rate payments related to SOFR are based on a hypothetical or face value known as the notional principal amount. The magnitude of the underlying financial contract is depicted by the notional amount, which is also used to calculate interest payments.

Interest Rate Basis: The reference interest rate is the SOFR. Contracts that make reference to SOFR state that interest payments will be calculated in accordance with SOFR, which reflects the cost of overnight cash borrowing secured by the U.S.

Notification of Interest Payments: Normally, the parties to a contract will decide on their respective payment responsibilities separately and then notify one another of the amounts due. This guarantees the payment process's strength and transparency.

Termination Clauses: The agreement may contain clauses that permit early termination under particular conditions, such as an important violation by one of the parties or a change in the parties' financial situation.

It's important to note that the specific terms and conditions associated with SOFR-based contracts can vary depending on the ups and downs in the market growth,and the preferences of the parties involved .

Using Swap To Transform Liability

Let's look at how it works from fixed to variable:

Suppose initially I had a fixed-rate liability and received variable interest payments through the swap. You effectively transformed your fixed-rate liability into a variable-rate liability. This can be useful when you want to benefit from falling interest rates.

Variable to fixed: Conversely, if you initially had a variable rate liability and paid fixed interest rates under the swap, you transformed your variable rate liability into a fixed rate liability. This can help protect against rising interest rates.

Using Swap To Transform asset

Using a swap to change an asset involves restructuring or changing the cash flows produced by an existing asset to bring them into agreement with particular financial goals or risk management techniques. The return profile, cash flow characteristics, or risk exposure of the asset can all be changed in this manner.

Steps to Transform an Asset Using a Swap:

- Identify the Asset to Be Transformed

- Choose the Fixed Cash Flow Profile You Want

- Negotiate and Execute an Asset Swap

- Swap Payments

- Cash Flow Transformation

- Objectives for Risk Management and Return

- Monitoring and Management

Role Of Financial Intermediary

They structure swap agreements, and they earn a profile by facilitating swap transactions.

Example: Banks-for lending and borrowing money

Financial Intermediary includes

-

Market Makers: Market makers generally participate in a variety of markets, including those for commodities, currencies, options, bonds, and stocks.

Example: a brokerage house that provides purchase and sale solutions for investors.

-

Day Count Conventions: It is the method used to calculate the interest accrued on fixed-income securities, such as bonds or loans, based on the number of days in a specific period.

-

Confirmations: Confirmations ensure that contracts are signed by the respective parties involved in the swap transaction.

Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage occurs when one asset can produce a particular outcome more efficiently or at a lower opportunity cost than another asset.

Let's look into example below:

For example, if a country is skilled at making both cheese and chocolate, they may determine how much labor goes into producing each good. If it takes one hour of labor to produce 10 units of cheese and one hour of labor to produce 20 units of chocolate, then this country has a comparative advantage in making chocolate.

Criticism of comparative advantage

Some of the notable criticisms of comparative advantage include:

- Assumption of Fixed Resources

- Ignores the distribution of income

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Dynamics

- Lack of Resistance to Shocks

- Income Inequality

Conclusion

Swaps are flexible financial tools that are important in modern finance for making up. They can be used for a variety of purposes, such as minimizing risk, reducing cash flows, and achieving particular financial goals. What are the points to remember about swaps?

-

Risk Management: Swaps allow market participants to manage various types of risks, such as interest rate risk, currency risk, and credit risk.

-

Types of Swaps: There are various types of swaps, including interest rate swaps, currency swaps, credit default swaps, and commodity swaps, each serving different purposes and markets.

-

Transition from LIBOR: The transition from LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) to alternative reference rates like SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) has had a significant impact on interest rate swaps and other financial instruments.

-

Risk and Reward: While swaps offer opportunities for risk management and financial optimization, they also involve risks. Parties should understand the terms and conditions of swaps and carefully monitor counterparty risk.

-

Financial Innovation: Swaps have been instrumental in financial innovation, enabling market participants to develop new products and strategies to meet changing market conditions and investor needs.